.

((RETURN TO BLKNZM ST. PETERSBURG FRONT PAGE))

.

The right to take pictures

START SOUNDTRACK

.

Walking around a city taking pictures is a fun way to kill time, without any particular plan, just getting impressions, looking at things. In the old days I was a lot pickier. Film and developing cost money. I would carefully choose what I wanted to photograph. Nowadays it costs nothing. So I just slurp up endless images from infinite angles, hoping for some coincidence to arise.

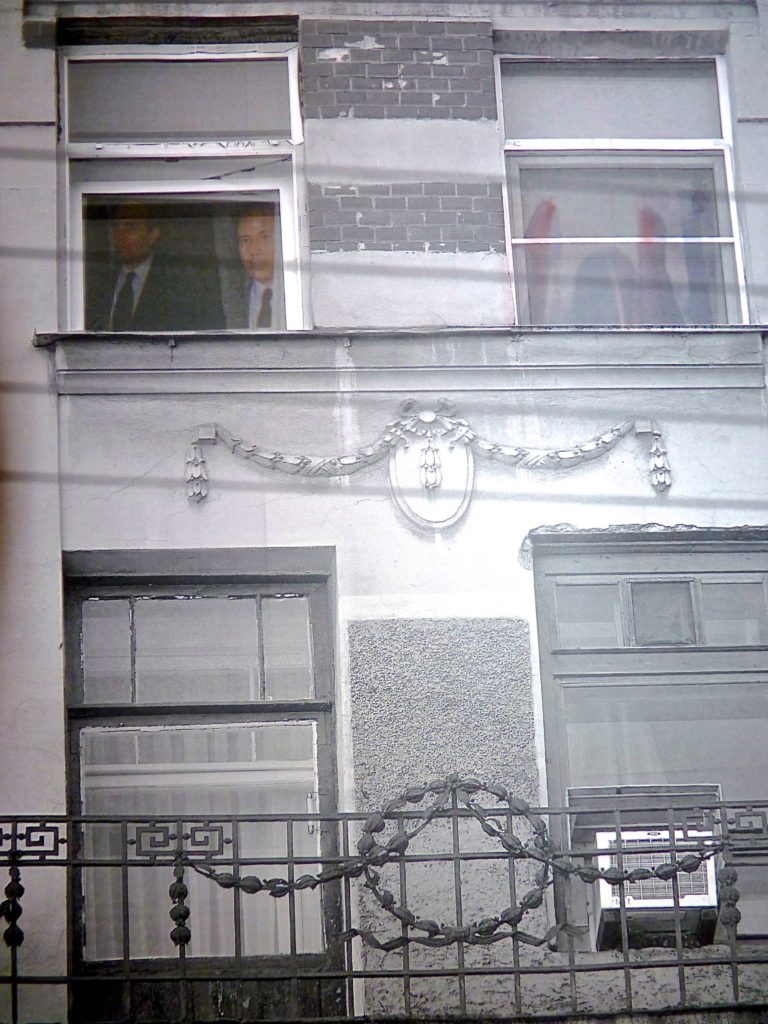

I was fixating on balconies and windows, maybe because I thought it was strange that such a northern, cold city like St. Petersburg would have any balconies at all. None of them seemed to be utilized, no plants, no household stuff like you might see in Mediterranean countries, no laundry hanging on lines. Finding them seemed challenging at first, but then the more I looked the more I saw. There was something disorienting about the transplant of a classical southern European feature into such a foreign place. It was like those counting games kids love so much, when they are bored on a long trip in the car. Out-of-state license plates, blondes and brunettes, brands of cars, that sort of thing. Budding pollsters.

.

When I got back to the hotel the desk clerk told me someone wanted to see me. Though I couldn’t imagine who, since I knew practically no one in the city, I followed him to the manager’s office. Three rather thuggish men awaited me. No, actually just two thugs. The third man was slight of build and more elegant. He did the talking. The other two stood silently near the door, one on each side of it now, hands joined in front of them.

The smaller man was very courteous and spoke good English. He wanted to know why I was taking pictures of windows. It was a good question, in a way. I had to think about it for a while.

Why do we take pictures of things? I mean, instead of just looking at them and enjoying them in the here and now? Do we really think a picture will somehow help us to take possession of them? Isn’t there a stupid feeling that if you have no proof of your passage, your trip to a foreign place might never have happened at all? Our photographs, even when we feel like photographers instead of tourists, are something of a ratification, evidence that we were actually in St. Petersburg and not hiding out in the basement or something.

Then there are all those other justifications. Taking pictures makes you look more closely at things. It helps you to find a key of interpretation, a single feature that lets you get into touch with a place, and compare it to other places you’ve been.

.

.

Maybe you observe things more acutely when you are taking pictures. You feel virtuous, because you are trying to really understand the place, not just passively accepting the reading of it supplied by guide books, documentaries, websites. Like taking apart a watch to find out how it works. Or opening up a TV set to see if there are little people inside it. Or like a doctor with a probe, scanning your insides to see what’s happening.

I realized that not a single one of these considerations would make a suitable answer to the man’s question, though… I didn’t think he would understand, and I certainly didn’t want to seem weird or eccentric.

.

.

Not only that: even as I thought these thoughts, I realized how pathetically lame they were. Excuses for something that really doesn’t make much sense, a replication of duplication, an exercise in futility, an attempt to arrest time and to capture memory where memory alone could suffice. My reasoning was an inherited and unquestioned transliteration of the thinking deployed to defend sketchbooking and easel painting, but with one very important defect: whereas the draftsman or the painter really did have to analyze his subject in order to reproduce it, thus engaging in a very intense and not very rapid tussel with reality, perception and sight, necessarily imposing his or her own interpretation on it that could then be communicated to his fellow human beings, the photographer, especially of my ilk, takes no time at all to really contemplate what he is shooting. Contemplation is inherently postponed, it’s in the nature of the act. There is even a sort of aesthetic credit assigned to the rapidity of the thing, the spontaneous act of pushing a button on impulse and only later realizing – or not – what had attracted you in the first place.

.

.

So I told the smaller guy I was doing research on architecture, studying the influence of other cultures on the architecture of St. Petersburg… and anyway, what was wrong with taking pictures of buildings? Isn’t that what tourists do?

“Very commendable,” he said, “research and learning are to be respected. But you see, people get upset about having pictures of their windows and balconies taken. They think someone might want to break into their home. Or someone might not be minding his own business. People have private lives, personal affairs they might want to protect from prying eyes. Nowadays photographs have a way of circulating that can be an invasion of privacy. Certainly you can understand that. But of course architectural research is important, for the advancement of learning. Please show me some credentials, if you can. Even on the Internet.”

Naturally I had no credentials. So he asked for the memory card from my camera. I hesitated. Thoughts raced through my mind. Is the right to take pictures of buildings, or people on the street, or cars, or anything else, a freedom protected by constitutions? I wasn’t sure. It didn’t seem that likely. In New York people get upset if you take too many pictures, especially in public places. On airplanes stewardesses have ordered me not to use my camera to take aerial views of illuminated nighttime cities, without ever explaining why. In Italy a policeman once prevented me from taking pictures of a police station, though it was adorned with very interesting bas-relief sculptures that had caught my eye. Maybe there is no such thing as the right to take photographs. I was once taking pictures on the Bowery, of what I assumed (correctly) were doomed stores and buildings, when some of the homeless-looking sidewalk denizens complained. I realized they might be afraid, if the pictures were published, that their relatives or former loved ones would recognize them in their present sorry state as street bums. Completely understandable.

And speaking of credentials, I realized I hadn’t seen those of my questioner either. I asked him to show me some credentials too. He just smiled.

.

.

In Germany I have been forbidden to make sound recordings in a department store. The security staff saw my microphone and not very politely ushered me off the premises. I was also denied permission to record the sounds in a public swimming pool. When I asked why, I was told that the law forbids taking pictures in places where children might be partially naked. When I said I was not taking pictures, they explained that the devices we use to photograph or to record sound all look pretty much the same, so to prevent pedophiles from invading the privacy of juvenile bathers the regulators had decided to ban any form of recording, whether of light or of sound.

“I am not a policeman, my friend. Let’s say my job is to protect the interests of certain people in the public eye. But of course I have very good relations with the police here. If you prefer, I can introduce you to some of them. I am sure they would be very curious to know why you are taking so many photographs, instead of simply enjoying the remarkably beautiful museums and monuments for which our city is rightfully renowned all over the world.”

In Berlin I once recorded the sound of enormous magnets mounted on cranes as they gathered and moved huge quantities of scrap metal at the port. Again, I had no camera. Some burly port workers challenged me and demanded the recordings. They were very menacing. Fortunately I was with a tall beautiful blond German woman, Bianka, with a lovely voice, who managed to convince them I was not a reporter, a terrorist or a corporate spy, but simply an innocuous artist in search of crunchy sounds.

In England the law does cover the right to take pictures. But evidently there are a lot of problems there, too. There have been protests about police and security harassment of photographers, especially during political demonstrations.

http://www.urban75.org/photos/photographers-rights-and-the-law.html

The American Civil Liberties Union has a page on photographers’ rights, too.

https://www.aclu.org/free-speech/know-your-rights-photographers

I said nothing about all this. I just smiled at the emissary of I knew not what authority, or what private citizen.

.

“Do I really look like someone who is planning robberies? Or a peeping tom? Or a spy?” The whole thing was oh so Le Carré, so spy movie-ish.

“Well frankly no,” he said. “You do not. So just this time we will overlook the rules. But don’t let us catch you prying into other people’s affairs again, or it will be trouble. Please enjoy your stay. I am very sorry to have inconvenienced you. But really, I am so impolite! As a citizen of this city, I owe you a warmer welcome. Can I offer you a drink? Here at the hotel bar?”

He glanced at the two thugs and they disappeared. We went to the bar. We drank some insanely expensive Italian wine. No one asked for money. We chatted about the beautiful sights, about how much he wanted to visit New York someday. He said he too enjoyed taking photographs. Could he just see what I had taken? For curiosity? From one photographer to another?

I didn’t see why not. The pictures were truly innocuous, I thought. He emitted little sounds of approval as the shots flipped by on the camera’s screen. “You are very accomplished. A very good photographer, indeed.” Pure flattery, the pictures were average normal amateur, at best. When I was finished, he asked me to flip back a few shots. He stopped me when we landed on a photo of a modern apartment building, seen from across the street. There were a few people on the sidewalk. What interested me was the balcony. I was planning to edit the sidewalk level out of the shots. He asked me to zoom in on the people on the sidewalk. A man and a woman could be seen, entering the building. Their faces were hard to make out.

“So you are not a paparazzi,” he said. More like a statement than a question. I said no, I was not.

“Listen,” he said, “I don’t want to make any trouble for you, understood? But you could just do me one little favor, to help me keep my job, to avoid problems for us both. Please erase this photo. If you refuse, nothing will happen. I am not threatening you. But if you would be so kind as to erase it, now, here before my eyes, I will sleep much better tonight. And so will you.”

.

.

“But why?” I asked. “At least tell me that first.” I was stalling for time, considering the idea of file recovery software, thinking about whether I should get upset or not.

“You see, in this country we do not like scandals. We have plenty of scandals as it is. We do not want bad stories, like your Clinton, or like that Strauss-Kahn person, or the French prime minister on his motorscooter. We believe there are more important things to worry about.”

“Maybe you’re right,” I said. “It wasn’t such a great picture anyway. I have three other shots of this balcony. Which I assume I can keep.” And I erased it.

He shook my hand and left. I took no more pictures in St. Petersburg. Not even at the Peterhof. For some reason I just didn’t feel like it.

CREDITS

Text, soundtrack and images by Steve Piccolo